Artist Annu Matthew Is Reclaiming The Cultural Past By Unearthing And Archiving Untold Histories

- IWB Post

- June 6, 2019

“Around 2.5 million Indian soldiers fought for the British in the Second World War and are largely forgotten in history. Those soldiers fought and died during the World War II which ended in 1945, yet their sacrifices were shuffled aside during the Independence struggle and the horrors of the Partition,” writes artist Annu Palakunnathu Matthew.

As an artist, it is the forgotten bits of history, silted in the oceans of time, that charm and agitate Annu the most. She believes it is in these ignored and untold bits of history that a major chunk of our cultural past gets lost. She has thus been constantly working to reclaim these chunks of cultural past and to throw light at multiple alternative historical narratives that remain sidelined.

What even is history? It is anything but a linear, coherent whole and way more relative than factual. To sum it up, there lies multiple histories both breathing and buried across times, geographies, and individuals.

An artist of the Diaspora, Annu shares that it is, in fact, her migrant identity that makes her “more cognizant of voids, losses, and erasures”, adding, “It is less nostalgia but more about understanding what is missing in these abysses.” This explains her preoccupation with the forgotten histories of those on the periphery of the mainstream narratives or the ones completely thrown out of it.

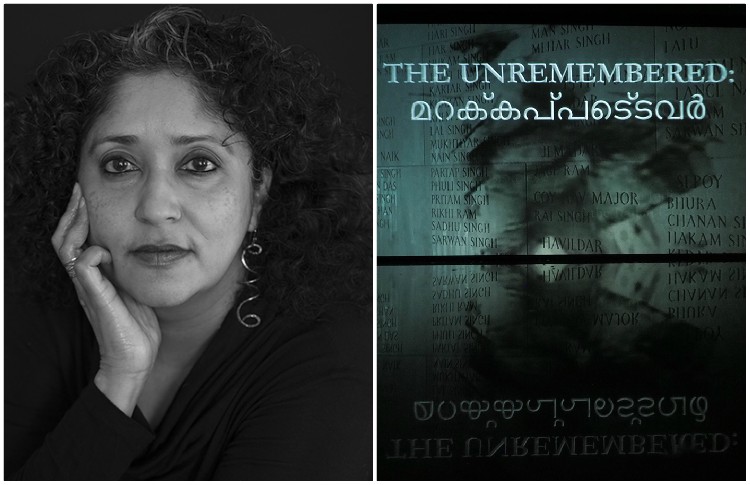

A Fulbright fellow, Annu is currently in India collecting stories and photographs of the Indian soldiers who served in World War II, their friends, and families. She aims to assimilate all their artwork and memorabilia into artwork to document and share their histories, so that they are not lost in the ravages of time. She exhibited an extension of the same project titled “The Unremembered” at Kochi Biennale 2019.

In a conversation that I recently had with Annu, she talked about the relevance of the project exhibited at Kochi Biennale, navigating through the idea of nationalism and patriotism as a diasporic artist, the importance of unearthing forgotten histories, and how hybrid identity is becoming the new reality in the global world.

Here are the excerpts:

Your installation “The Unremembered” at Kochi Biennale pays homage to the Indian soldiers from the Italian campaign of World War II. Please tell me a little about the experience.

By 1945, two and a half million Indians had stepped forward and volunteered to take up arms for their British Colonial rulers during World War II (WWII). They fought in the mountains of Burma, the hills of Cassino in Italy, and in the deserts of North Africa. Thirty of them won Victoria crosses, and more than 87,000 died. Yet, in India, they remain uncommemorated and unremembered.

CLIP from The UNREMEMBERED – Indian Soldiers of the Italian Campaign, World War II

The UNREMEMBERED is about the 2.5 million Indian soldiers who fought for the British in World War II and are largely forgotten in history because of their politically complicated role. Having fought and died during the second World War, ending in 1945, their sacrifices were shuffled aside during the Independence struggle and the horrors of the Partition.

Millions of South Asian veterans of WWII returned home just as the subcontinent was preparing to violently split into the two independent countries of India and Pakistan. I stumbled on this story during almost a decade-long research on the Partition of British India. During that time, I collaborated with the children of Partition, and created artwork that tells their stories and draws attention to the continuing impact of Partition’s pivotal moment in history. The project is called An Open Wound.

THE UNREMEMBERED builds on the research I undertook for this earlier project to create new work that reveals a layered and largely unknown history, giving voice and a face to those who sacrificed so much. It seems unbelievable that the contributions of such a large number of people have gone unrecognized. Doubly so with the recent news and attention about the Indian pilot captured and then returned by Pakistan to India.

How do you, as a diasporic artist, navigate the ideas of nationalism and patriotism?

That is a really good question, one that I often ponder. I think being both an insider and outsider (someone who was born in England, grew up in India and now lives in the US) allows me to question what nationalism and patriotism in both my culture of origin and in the culture where I live now mean. This role allows me to appreciate the past histories in each country and to explore untold histories, with a dispassionate approach. It allows me to view these histories through a different lens.

Do you think that the rhetoric of art transforms/fluctuates as you transit between two countries?

Some art transcends borders. Other valid forms of art get transformed when shown contextually. I think this is similar to my own fluid national identity; there isn’t a black and white answer. I hope that the artistic works of mine that sometimes need more context can also be seen and appreciated more globally.

You often wreathe together the historical narrative with the contemporary. There has to be a message here. What message and lesson do you think the contemporary generation needs to learn from its history?

As philosopher George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The more I learn about history and its cyclical nature, the more I believe this quote. Our educational system doesn’t do a good job of illuminating our cultural past so that we can empathize and learn from it. I can give you an example. When I studied in India, we never learned about the details of Partition. We were only taught that the region was divided, about the British and about Gandhi’s non-violence movement. We learned nothing about the horrors of what happened. I only learned that at least four of my classmate’s families had gone through Partition 25 years after I finished high school. Back then, I never learned about the traumatic impact Partition has left on our country, one that reverberates even today. The recent military dispute is an example of this ongoing open wound.

Open Wound_Book_India_Map_Ipad

Installation of videos from Stories of Partition- Open Wound

In your work, I detect a certain fascination or affinity for the forgotten and ignored bits of history. Can you please throw some light on the same?

I wish I could say that I was a brilliant history student. I was NOT! Coming from England at 12, I struggled with the names of all the kings and kingdoms and I tried to understand the complexity of the places we now know collectively as India. But it is true that I do have a fascination with the ignored bits of history. I see my work as reviewing of histories.

Still and moving imagery are intrinsically connected to history and memory, a fact I use as a tool to prompt viewers to reconsider their own perceptions of history of those outside of the majority. This approach crystallized when, just after graduate school, I read Ronald Takaki’s A Different Mirror, which reframes the history of the United States through the voices of its non-European peoples. The book reshaped my outlook on the ways different people perceive the same historical events based on their cultural experiences.

Memory is yet again very integral to the aesthetics of your artwork. In fact, nothing binds all of your projects together like memory does. Let us explore the idea of memory as something more tangible and less of a figment of mind easily altered by the ravages of time. Please talk about the importance of memorabilia and objects from the past as a valuable part of our lives, culture, and existence.

That’s very perceptive. Only now, with the luxury of time, am I able to look back at my work and realize that the over-arching theme that connects the work is memory. Where does that come from? I think it comes from multiple threads – from having lived in multiple cultures and the unique memories from each place, from having left my culture of origin, and from losing my father when I was very young. All these things make me more cognizant of voids, losses, and erasures. It is less nostalgia but more about understanding what is missing in these abysses. Also, I have long been fascinated by photography and time-based media that are rooted in reality. That is media that are integrally connected to memory.

In your project “To majority minority” you throw light on the contemporary social constructs of America. There is nothing more important than the freedom of expression for an artist. Given the current political situation of Trump’s America and as a migrant artist living there, how do you assert your creative freedom?

Through my project “To Majority Minority,” which started almost five years ago, audiences obviously know my perspective on immigration in America. In today’s reality, it has been difficult for me to reconcile what I thought of as the ideals of what America was vs. what it is today. As a result, I am struggling with my own creative voice in the face of the current President’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. I don’t want to create a parody for the sake of creating work, nor am I in the frame of mind to collaborate. So I haven’t created any work about this new paradigm. But I am working hard to exhibit, present and talk about my existing work that has taken on a new relevance and which directly explores the immigrant experience. I have also become more active in politics, rallies, and social movements.

While artists and thinkers all over the world have hitherto talked about the brokenness of migration, how about we talk about the strength of the multicultural/cosmopolitan identity? How has it empowered you as an individual and as an artist?

To clarify, I don’t think all artists and thinkers talk about the brokenness of migration. There are many artists whose immigrant voices are strong and ask us to view their new countries with fresh eyes. Robert Frank is just one of many.

I wouldn’t be able to do the work that I do if it wasn’t for the transnational lens of my experience that resulted from my formative years being spent in three cultures. I think this hybrid identity allows for more acceptance of difference, for more extended cultural consideration, making me something of a cultural chameleon. This identity is becoming a new reality in our more global world.

1_Identity_Virtual Immigrant

The Virtual Immigrant draws on the experience of call centers workers in India. These Virtual Immigrants become Americans for a workday but remain physically in India. To work in these call centers, Indians study American culture and either neutralize their Indian accents and/or adopt American ones.

If you, a family member, or a friend served in World War II, share your stories before those memories are lost to history. You can reach out to Annu at www.indiansoldiers1945.com.

Cover picture credit: David H. Wells

Artwork picture and video credits: (c) Annu Palakunnathu Matthew and sepia EYE, NYC

- 0

- 0