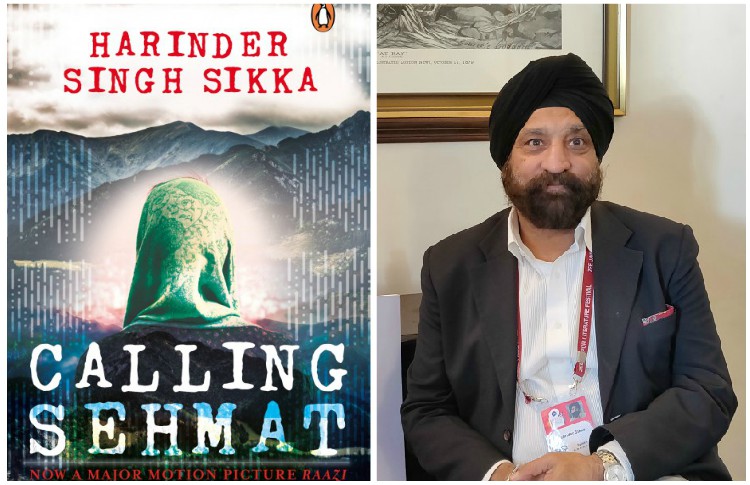

Amandeep Sandhu Reopens His Childhood Chapters To Explain The Plots Of His Two Famous Books

- IWB Post

- October 19, 2017

Amandeep Sandhu is a celebrated Indian writer and has authored two books, Sepia Leaves and Roll of Honour. His books are said to be an abstract of his personal life more than the works of fiction. During a conversation with the writer himself, IWB tried locating the teenager boy inside him that encouraged Sandhu to begin writing. Excerpts below:

Let’s start on a lighter note. Describe your day to us as if you are penning it down in a journal.

I just returned from a trip to Europe. I had got bogged down working on my next book, a travelogue on Punjab. I went to slip into being a traveller, to loosen up, to relax, to encounter other cultures and nations and histories. When I came home, I opened the windows, dusted the racks and cleaned the floor up, put clothes to wash, and got a haircut, and met friends who came over in the evening.

After writing two books that document some crucial parts of your personal life, do you think you’ve evolved in some way? Have the hundreds of pages of exploration changed anything?

Even after writing those hundreds of pages, I feel even more uncertain about myself. The more I explore myself, the more my way of describing myself through labels dissolves. Yet, I feel satisfied with my attitude to life. It is this: do not be defined by anyone else, seek your own language and ensure it cannot be appropriated.

When was the first time you wrote your feelings on the paper? Do you still have that draft?

More seriously after I started working at age 26 or so. But before that, I have sat crying in front of white paper not knowing how to write. No. I have burnt many diaries in my life.

Tell us the story behind the title ‘Sepia Leaves.’ What other titles did you have in mind?

I wrote the book as notes to myself to prepare to live with my parents from whom I had stayed away for over two decades. My mother was ill (she suffered from schizophrenia) and my father had sent me hostel early when I was merely five years old. Through school, college, university, I would see my parents only for a few weeks every year. Then when I found a job in Bangalore, had settled down, my parents wanted to come and live with me. I was their only support. I asked myself: who are these people? What is my connection with them? Before accepting them back into my life, I needed to make peace with them, I needed to process my relationship with them, process the denials I had practiced for years. At some point I saw the notes becoming a draft, the draft of 600+ pages becoming a slim book of 185 pages. It was on the night my father died that I found the back and forth structure of the book.

In the process, the names of the drafts were B-25 (the stigmatized house where the story occurred), In Sanity (a play on the idea of normalcy), Knife Among Pears (if I had projected the fight as a theme to make the book racy), many others I do not remember now but finally Sepia Leaves (Sepia being the colour of the memory and Leaves being leaves of an album). I now feel the title is a bit obtuse, a little tangential, and a more direct title would have been better. But now the world knows the book with this name, it anyway belongs to the world. It is fine.

Having changed many jobs and worked as a farm-hand, woolen-garment seller, shop assistant, tuition master, teacher, journalist, etc., how have these diverse experiences shaped your personality?

Everything adds up. What this kind of a multi-job life does is rob you of your assumptions and entitlements you inherit at birth and are culturally indoctrinated to believe about yourself. It makes you humble. I learned from every job, from every aspect of work, and I hope it shows up in my writing.

Amidst the struggle, what kept you going?

The desire to be free. At the core of our entire effort is the need to feel free from systems that seek to oppress us. These systems could be political, social, ideological, monetary (as in poverty), and all of them play out in language, in how we define systems. It is in defining the systems that the power shifts from an individual to a system and we are appropriated. Once appropriated it becomes an uphill task, a struggle to free ourselves. That is why I said above, avoid being appropriated. I feel the core goal for every human being is to live with dignity. That is why my aim as a writer is to use language to give dignity to those we ostracize from society.

What was the most challenging part of writing the two books – Sepia Leaves and Roll of Honour?

With the first book, I was challenged the most trying to name it to my satisfaction. In the second, the name was clear, but I was challenged the most in trying to write the first line. In the current book that I am writing, I am challenged the most in how to open it, what should be its first chapter. I am just a very slow, laborious writer.

The other aspect that always challenges me is how much detail to provide so that the reader does not feel overwhelmed. You see, every book has a narrative logic. Narrative logic is the logic created to sustain the book. This narrative logic is infinitely smaller in scope than the logic of everyday living in which random cruelty takes place. I can’t put everything on paper for doing that will leave the reader as bewildered as I am when I start writing. I write testimonial fiction to deal with my experiences, to gain control of my life, my sense of my existence. So that is the challenge: to edit life experience into a narrative that I can communicate with an anonymous reader.

The books made you revisit some emotionally-straining life moments. How did you find your way back to happiness and peace while writing?

I write to bring peace to myself. For me writing in itself is a meditation. Allowing oneself to mediate teaches you how to meditate. That is the strange thing: meditation and writing teach you how to do them. I guess like walking and swimming. I write to learn to organize my thoughts and feelings because I believe and have experienced that writing shows you its inner logic. I come to writing each book after great roaming and wasting a lot of time and energy but when I reach that place there is no emotional strain. In fact, a confession: when a while after the publication I read most of my writing, I do not believe I have written it. It truly is someone else from my usual self who writes. Though that self is also part of me. Yet, it is best left undefined, as long as it writes.

In ‘Roll of Honour,’ you talk about the bullying and sodomy a young boy had to face at his boarding school. Share your personal experience of dealing with sexism as a teenager and how it affected your life as an adult?

My book comes from experience but seeks to connect the personal with the political. It presents a distillation, the essence of the experience of the time period shaped by external compulsions and circumscribed by the class by class stay at school for a full seven years. The book explores relations between a dominant center and an erratic state (Delhi and Punjab, which is by extension Sikh) through the metaphor of power in the school organized on lines of corporal punishment. While the guns dictate the center-state relations, the penis dictates the relationships between seniors and juniors in school. Sex becomes a tool of power.

Yet, though I carried bruises from experience for a long time, maybe still do, I cheated when I populated the book with characters. While writing, I realized the ones who had bullied me were also victims of their circumstances. Their real fault was they did not know how to end the cycle of violence. I wanted the book to terminate the cycle of violence in my life. So, I made sure no character is easily identifiable.

It was trauma. In fact, I wrote to understand my fear. Upon writing, I learned that the bad we seek to fight outside of us originates within us. It also did something which I consider positive: my orientation towards sex changed. To me, sex is no longer about power or domination but about warmth and shelter. Also, I believe, sex is not gendered. That is why in the book I contrasted cold, humiliating sodomy with warm, tender, gay love. I feel, in harsh environments, our need for warmth brings us closer to each other. The gender does not matter. What is important is if we feel secure in the embrace of a loved one. Do we, through the act of love, reconnect with ourselves? Love making to me is not about performance but about acceptance – of us and the other – and about play not goals.

What was the reaction of your family when the books got released?

I have no immediate family. I have no siblings. My father and mother were both gone. My father had seen both drafts, and his almost last words to me were: for me, you have become a writer. Ironically, to me, it was his sensitive self who was truly the writer. After much coaxing and effort, towards the end of his life, he wrote his life story in seven notebooks. They are with me. Someday I will compile them.

When ‘Sepia Leaves’ released, the ones happiest was my cousin Minni and my aunt Bibiji who traveled – for the first time in her life – to Delhi from her small village in Punjab. When RoH released, the one happiest was my then partner and now wife, Lakshmi. I really do not know how the rest of the larger family took the book. I do not think they have read it.

Did the people who bullied you ever get back to express remorse?

The response from my schoolmates was mixed. Many classmates liked it and called to share their stories with me. I learned that many of them had led scarred and broken lives. Many seniors loved it, but some remained in denial saying: our times were not like this. I am okay with that. I wrote to break away from the cluster. Whether one likes it or not, the book is based on facts, and it prompts every parent to think about the lives they are creating for their children. In that lies my satisfaction.

Talking about the publishing procedure, did you face any challenges?

Even if I do not count the notes and draft stage, the book itself took five years. Every major publisher had rejected it. Yet, on the day of its launch, a big publisher offered to buy it out. Then they sat on it for another eight months. When it came out, owing to an internal tussle, the publishing house did not promote the book or make it available in shops. For a long time, I was getting requests from strangers for copies of the book. I would buy copies and send them to readers. I still get these requests. What had happened was that an excellent first review appeared in The Hindu and the word about the book spread. It was helped by psychiatrists and people from the mental health community promoting the book. Now I am given to understand it is a cult classic among students of psychology and psychiatry. It is prescribed in leading medical institutions and elsewhere.

If you could rewrite any chapter of your life, which one would it be?

Honestly, nothing. I got what I got; I made of it what I could. There is no rewriting history or biography.

Having lived in many cities across India, the memory of which city leaves you homesick?

This one is too hard to answer. Each city teaches you new things. Frankly, I actually miss none. I actually belong nowhere. When I do, I belong to my heart.

Which book are you currently reading?

A new friend has sent me a book called Watercolours by Lidia Ostalowska. It is based on a real-life story of a painter, a prisoner at Auschwitz. Other than that, on my travels, I was browsing city brochures during my travels.

What’s the most unusual thing we’ll find on your work table?

It is bare. Just this computer.

Do you believe in a ‘perfect setting’ to get you in the flow of writing?

I do. When my mind is calm, I unconsciously put on Hindustani classical music to play in the background as I sit down to write. Kabir and Kumar ji remain favorites but I uncomprehendingly listen to masters like Kishori tai, Bhimsen Joshi, Bade Ghulam Ali, Mallikarjun Mansur and so on.

Lastly, what’s in the future?

For a few years now I have been working on a book on Punjab. I am calling it a travelogue, but it obviously is more than a journey book. It seeks to explore and address the idea of Punjab that has stayed with me all my life but which is described and labeled by everyone I know, every book or article I read, rather inadequately. I hope to fill the gaps in my understanding of what Punjab means to me. There is another novel called The Memory Maker on migrations and migrants in Punjab – the east India labor force – which is languishing in drafts. I need to finish it.

All the best, Amandeep!

- 0

- 0